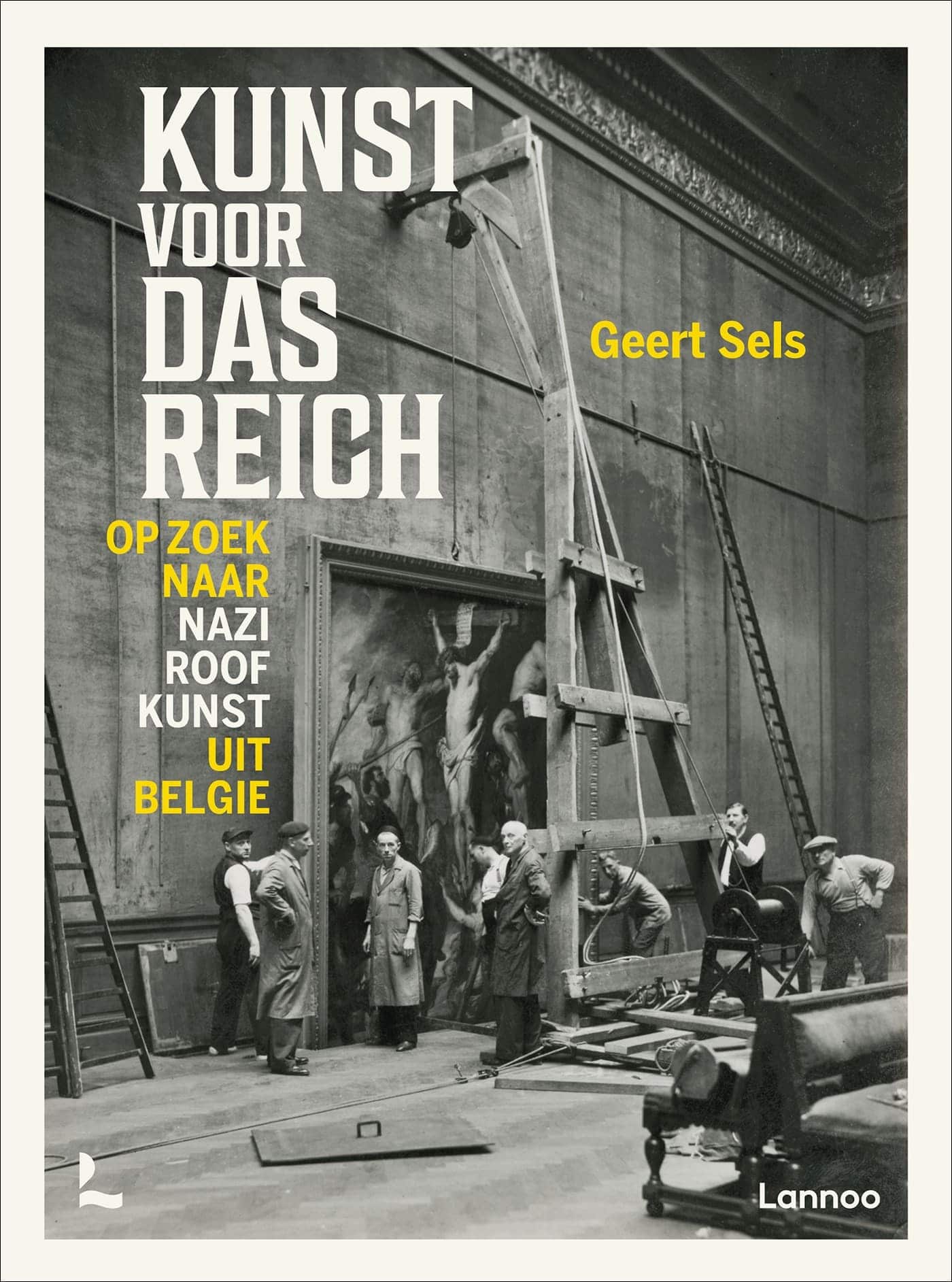

Art for Das Reich: The Forgotten Stories Behind Nazi-Looted Art

Investigative journalist Geert Sels spent eight years researching Nazi-looted art in Belgium. In Kunst voor das Reich (Art for Das Reich), he brings many histories of robbery, collaboration and restitution to light for the first time. His book is also an appeal to the Belgian government to tackle this issue thoroughly.

In the mid-1990s, stolen Jewish property suddenly became a topical issue in Western Europe. In 1998, an international conference on looted art was organised in the United States. It concluded with a non-binding statement in which principles were formulated for dealing with art confiscated by the Nazis. Researchers in various countries set to work to chart the nature and scope of the problem. Museum collections were examined, and governments drew up guidelines for returning looted artworks. France, Great Britain, Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, among others, set up committees to investigate and assess applications for restitution.

Initially, these developments ran parallel in many countries. The confrontation with the suffering hidden behind the many existing artworks brought a chapter to the fore that had seemingly been closed. The readjustment of the historical self-image that this caused was accompanied by heated debates and high emotions. In the Netherlands, a request submitted in 1998 for the return of artworks from the merchandise inventory of the Jewish art dealer Jacques Goudstikker led to years of media attention, and the German Gurlitt affair in 2013 caused worldwide commotion.

During the occupation years, prices on the art market broke records

In the countries surrounding Belgium, dealing with what has come to be called looted art has acquired a firm place in social consciousness. This has also translated into political urgency. Belgium seems to have occupied an exceptional position in this for a long time. Is there no Nazi-looted art in Belgium? And is a passive attitude towards the problem therefore justified?

After eight years of research, Geert Sels answers these questions resolutely in the negative in Kunst voor das Reich: Op zoek naar naziroofkunst uit België (Art for Das Reich: In Search of Nazi-Looted Art from Belgium). He backs this up in a hefty overview consisting of almost four hundred pages of text, divided into seventeen thematically ordered chapters covering a time period starting with Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 and ending with the recent political developments in Belgium. The book is also written as an explicit appeal to the Belgian government to approach the issue more actively. To this end, Sels has traced the surviving relatives and heirs of the original owners and actively brought his findings to their attention.

'Four trees' by Egon Schiele is one of the works featured in 'Art for Das Reich' by Geert Sels

'Four trees' by Egon Schiele is one of the works featured in 'Art for Das Reich' by Geert SelsThe focus of Kunst voor das Reich is on paintings, but the themes covered are broader, such as loss of possessions, robbery, collaboration, recovery and restitution. Also discussed are the ups and downs of the many Jewish refugees in Belgium, the art hunger of Nazi leaders such as Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring, the expropriation of Jewish businesses, the confiscation of household goods of deported Jews and the role of transport companies. Sels also sheds light on the dynamics of the art market, where prices broke records during the occupation years. A large part of the art that ended up in Germany from the occupied countries was therefore not stolen but sold willingly and often for a large profit.

A merit of Kunst voor das Reich is that, from the beginning, Sels illuminates the international context of the problem of robbery and restitution. After Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Jews fled Germany. While in the Netherlands approximately eighty-five per cent of the Jewish population had been there for several generations, in Belgium, more than ninety per cent of Jews were immigrants or refugees. Kunst voor das Reich begins with a “procession of fear and hope” and shows how the position of refugees was extremely precarious before, during and after the occupation years. Adrift and often in desperation, artworks taken along were sold in order to stay in the new place of refuge, for living expenses or to pay for a possible journey.

A large part of the art that ended up in Germany from the occupied countries was not stolen but sold willingly and often for a large profit

In that context, Kunst voor das Reich

describes several transactions which cannot be regarded as robbery or confiscation. Yet through the life stories of the original owners of the paintings, an oppressive image becomes clear. For example, Sels uncovered cases in which Jewish refugees relinquished artworks in order to secure a visa from the Belgian authorities. Museums also acquired art at advantageous prices, while it was known that it concerned the property of Jewish refugees. A tragic example is the Austrian art dealer and restorer Moritz Lindemann. After years of grasping at straws, he reported to the German authorities in Brussels in January 1944 and then disappeared without a trace. Lindemann himself “vanished in the mists of time”, but the Portrait of a Woman by Govert Flinck and the painting Pupils of Emmaus, works of art that he donated to the Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels in 1941, are still there.

Between the lines, Sels provides insight into the course of his research. This results in fascinating stories. It also shows the unconventional paths he sometimes had to take in an attempt to uncover “the full story”, through missing archives, destroyed files and fragmented documentation. A good example of this is the reconstruction of the history of the gallery of the Jewish art dealer from Antwerp, Samuel Hartveld, during the occupation years. With tenacious detective work, Sels traced documentation spread over fifteen archives at home and abroad. The story unfolds like a detective novel in which what appears to be a simple letter takes on a whole new meaning after an extensive analysis of handwriting.

'Beer garden near the Havel under trees' by Max Liebermann only resurfaced at an auction in Cologne in 2018.

'Beer garden near the Havel under trees' by Max Liebermann only resurfaced at an auction in Cologne in 2018.The international scope is also evident in trade and robbery during the occupation years. After the German invasion, national borders became prison walls for Jewish residents, but art dealers, buyers and German museum directors could come and go freely. Because the “powerhouse of the persecution” was in Berlin, as historian Jacques Presser noted, many aspects of the robbery of Jewish property were largely the same in the Netherlands and Belgium, despite differences in local circumstances. Numerous organisations and individuals involved in the acquisition of Jewish property were active both in Belgium and abroad. According to Sels, one of the greatest insights in his research is the fact that Belgium took up an atypical position, since works of art often did not end up directly in Germany, but via a detour through France or the Netherlands.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, inspect art treasures stolen by Germans and hidden in salt mine in Germany.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, inspect art treasures stolen by Germans and hidden in salt mine in Germany.© U.S. National Archives

After the victory over the Nazi regime, the Allies tracked down the stolen and voluntarily sold works of art in Germany. More than a million objects were collected, registered and distributed in the central Allied art depot in Munich. Representatives from countries such as France, Belgium and the Netherlands tried to claim works of art on the spot. Sels points out that the repatriation of art was less avidly pursued in Belgium than in the Netherlands and France, countries that gave greater priority to tracking down art and had better information. As a result, considerably fewer works of art were returned to Belgium (1,155) than to the Netherlands (6,891) and France (more than 30,000).

The Allies sent the art back to the country from which it had arrived in Germany. As a result, after the occupation, artworks of Belgian origin were also returned to the Netherlands or France. Sels regards the principle used by the Allies as a systematic error, although it can also be interpreted as the frayed edges of a process that aimed to achieve as much as possible in a short period of time. During his research, Sels found dozens of artworks that are now in the Netherlands, France and Germany. He raises the question of whether these should be transferred to Belgium after all. But can heirs there count on an independent and transparent assessment of a possible restitution claim?

With Kunst voor das Reich, which has now been published in Dutch and French, Sels has delivered a multifaceted and detailed pioneer work on a long-standing gap, laying a solid foundation for further research. Thus, he has managed to rescue many unknown histories of people and artworks from oblivion. Through the attention to the international context and detailed recording of myriad individual histories, Kunst voor das Reich is also a valuable reference work for interested parties and professionals within and outside Belgium.

Geert Sels, Kunst voor das Reich. Op zoek naar naziroofkunst uit België (Art for Das Reich: In Search of Nazi-Looted Art from Belgium), Lannoo, Tielt, 2022, 432 pages